I am already long into bed by the time the sun sets at 10.30pm. The long daylight hours I discover here on North Uist, part of the island chain of the ‘Outer Hebrides’, are a joy that after years near the tropics I’d almost forgotten.

What brings me here?

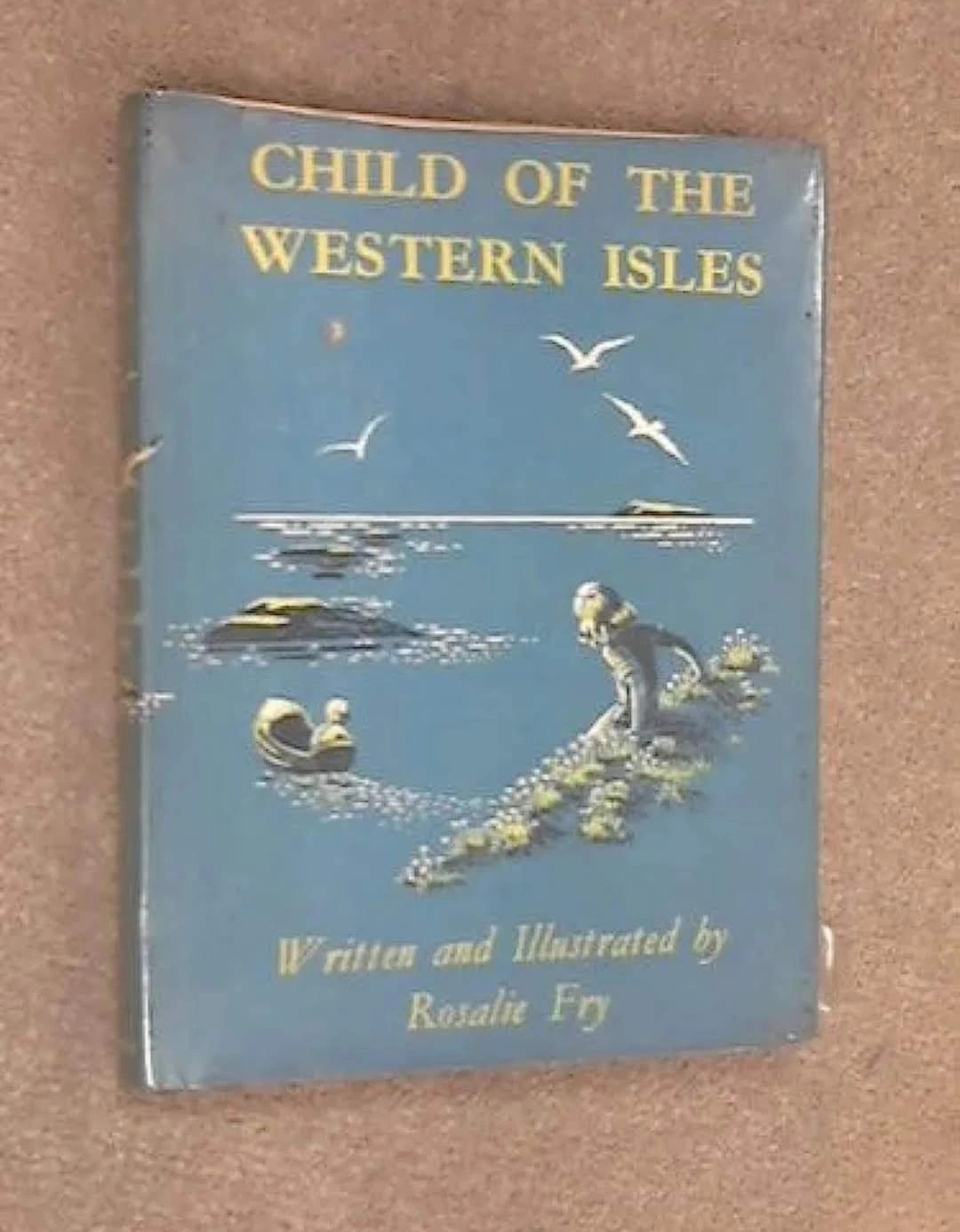

Two months ago, a request on the HelpX website caught my eye. This remote chain of islands off the West Coast of Scotland has long held a deep place in my heart for it forms the setting for my absolute favourite book as a child, the one I took out from the children’s section of the Oxford City library nine times. For my 8th birthday, much to the relief of the librarian I imagine, my mother gave me my own copy. (I see it is still in print, curiously now under a different title, ‘The Secret of Ron Mor Skerry’).

In brief, a young girl is removed to live in London when her island home is cleared of people, but as an older child returns to stay with her grandparents, finds her long-lost baby brother being brought up by the seals on their old island, with the consequence of which is they all move back there to be a family together. Even today, recalling this tale moves me to tears.

Such is the power of a well-crafted novel that as my ferry comes in sight of the first islands, I find myself drawn inside the story. I can sense the feelings of the different characters (including ‘Chieftain’ the seal !) and so well- illustrated with simple line drawings by the author herself are the people and places, that being here seems completely familiar and somehow feels right. If you ever gift a book to a child, maybe it will do the same?

I have memories too of being here with my family 60 years ago, a happy time with my father still living. While my mother headed to the beach to body surf Atlantic breakers on a plank of wood, my botanist father would have searched for unique moss species. I sense I simply splashed happily in the shallows while my older brothers fished for trout in the lochs.

For six weeks, I will stay in the home of my host ( whom I will name ‘Morag’ to protect her privacy), a crofter who has lived here all her life. Morag’s 90th birthday gift from her family was a surprise trip to London, the furthest she has ever travelled. “Ooh, I so enjoyed it, it was lovely. There is so much to see,” she tells me. I sense a hint of wistfulness at sights unlikely now to be seen: travel to and from these islands requires resilience, even for those not in their tenth decade.

Travelling here

Morag’s 95th birthday next week is an occasion for the family to gather. For her only daughter who runs a bed and breakfast with her husband on the neighbouring island of Barra, it means a 40-minute boat ride assuming the ferry is running. It doesn’t always.

For grandchildren who live on the Mainland’, a visit takes planning. The option is ether a 5-hour ferry journey ( I took this with my bicycle) out past the windswept grey stone houses of the port of Oban to their home on Barra, and on by the second ferry, or a drive further north and across to the town of Uig on the west coast of the Isle of Skye. Thence it is only a 2-hour ferry ride, easier for those whose stomachs fail at the thought of Atlantic seas.

Work and play

In the meantime, being 30 years younger than my host, I complete small tasks around the house and garden which have become a challenge. This morning, for example I take the ‘crochan’, an implement resembling a pirate’s hook, that is designed to harvest potatoes from the sandy machair soils. It becomes a perfect tool to rid stony paths of weeds as well. My host’s daughter, a fellow ecowarrior, has requested that I begin a compost heap. Of course, I need no further incentive! I layer weeds, food scraps, sheep dung and grass clippings into a sturdy heap, and now wait, curious if any self-respecting composting bacteria will handle these temperatures and the chill wind. The latter certainly challenges me!

This crochan harvesting tool seems a symbol for life on North Uist. Like the ground-nesting birds on this treeless island, local people have adapted their lifestyle to the unique surroundings. Morag insists I take every opportunity to explore so I join others on the village’s annual ‘nature walk.’ The sandy flower-strewn ‘machair’ soils close to the seashore have a precious ecosystem unique to these islands, and I’m keen to learn more about how such areas apparently thrive under the traditional crofting lifestyle.

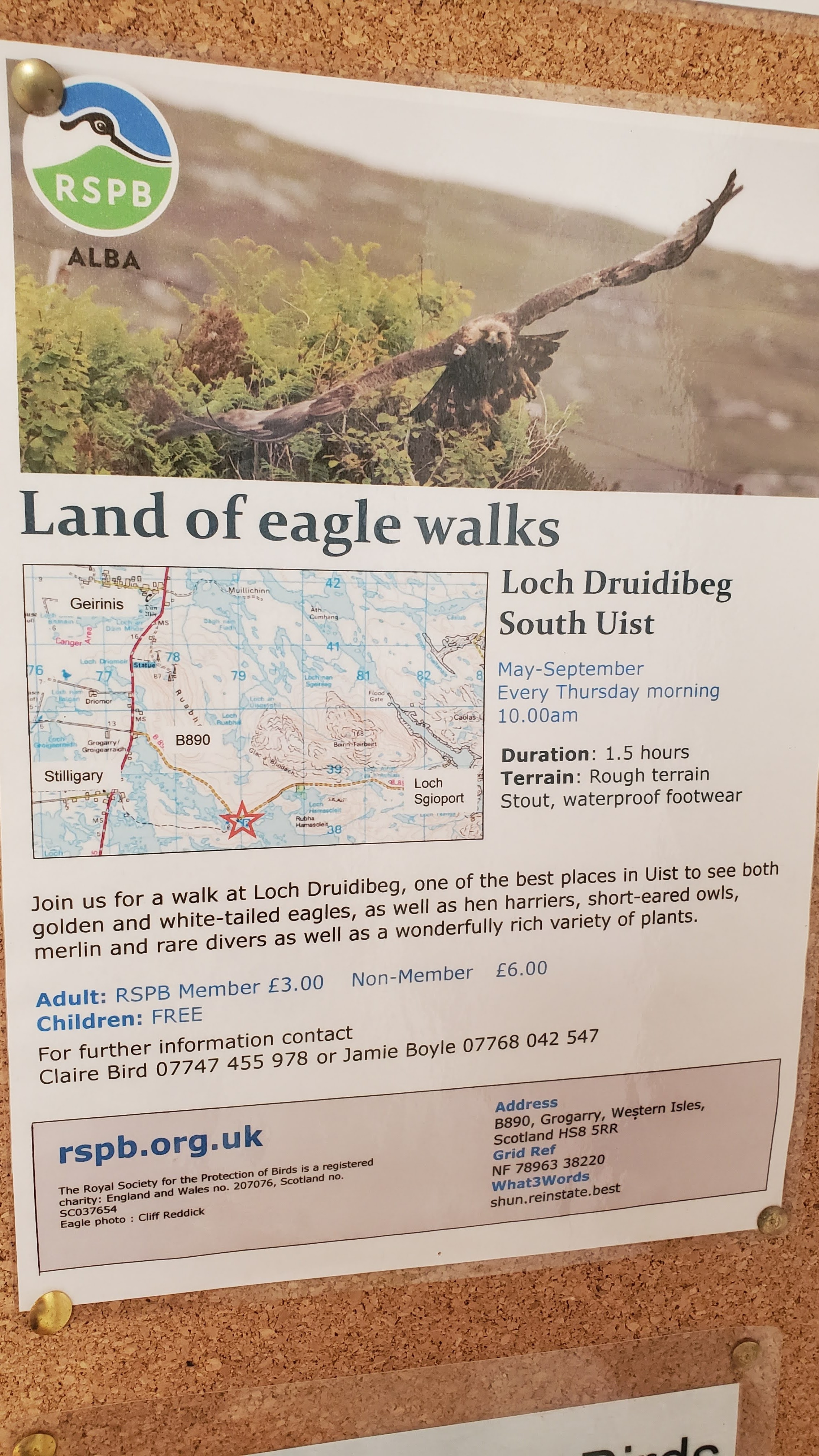

Skylarks and meadow pipits flitter as local ecologist, Jxxx, shares snippets from his extensive knowledge of the ecosystem. He’s a local man, an ‘incomer’ (I love this non-prejudicial term) who arrived from England 30 years ago to take up a conservation role with the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB), married a local and has never left. A sudden downpour does nothing to quell his enthusiasm ( I’ve heard how his father-in-law still doesn’t believe Jxxx has ‘done a day’s work in his life’, so clearly does he enjoy each day at his job!) and as we shelter in the lee of a barn we nibble hogweed seeds and explore whether wild carrot roots smell carrotty (they do).

As seems the norm here, the rain shower soon shifts. Cautionary cries from Lapwings and Oystercatchers acknowledge our arrival on the machair. This coastal strip seems a raucous multi-hued dance floor of wild flowers, while fallow cropping areas are brilliant with yellow marigolds. The traditional seaweed-fertilised potato plots, may seem more sombre but they are perhaps simply too busy growing in what looks almost like pure sand to spend time dancing in the breeze.

On the other side of the dunes, an outgoing tide begins to expose the tidal flats. Rare wading birds feed there ( humans too: records from 1901 list a weekly dispatch of 20-30 tons of winkles and cockles by steamer to Glasgow and thence to London fish markets).

Rare ecosystems

The RSPB and the Scottish government support crofters to adapt modern farming techniques to protect local wildlife. While early cutting of the special local varieties of oats and grasses grown for winter feed achieves a second silage crop in contrast to the single crop achieved through traditional haymaking, cutting these essential nesting habitats too early is a risk for young fledglings. Farmers are asked to leave the harvest as late as possible and to alter their harvest cutting plan to avoid corralling birds into a final central cutting area.

Such changes appear to be working for the rare Corncrake: there’s been a halt to a previous rapid decline in numbers. This iconic bird with a croaky song is a migrant that overwinters in central Africa. These days the islands of Uist are their main summer habitat; I’m told Corncrakes used to be so numerous and croaked so loudly, people couldn’t sleep at night. Jxxx tells me there is one nesting near the seawards end of Morag’s croft, but it certainly hasn’t yet kept me awake! I’d like it to…

Another bird conservation challenge is getting farmers to co-exist comfortably with Sea Eagles. These were reintroduced to the islands from Scandinavia, a controversial move. These rare giants share the air above the moors here with their even larger cousins, the Golden Eagles. While farmers believe sea eagles are a serious predator on young lambs, recent research at local nest sites suggests their diet is mainly fish and small mammals such as rats and ferrets, and that lambs taken are often carrion, dead long before they were ‘harvested’.

For now, I put these giant eagles in the same category as otters: much-talked about creatures I long to see, but havent. Yet. It’s not for want of trying: I search each time I bike past lochs and across the moors, albeit not sure how they would look. Today though I’m focused on finding Sand Martins and Frog Orchids, they seem easier!

Seaweed has long been an iconic part of the crofting lifestyle. It’s an essential nutrient applied to cropping land during the winter (history tells that appointed scouts would raise a signal to notify fellow crofters to hasten to the beach with their carts when plentiful quantities of ‘seaware’ washed in and lines were drawn down the beach for the equitable sharing of such bounty). It was also the main source of monetary income 200 years ago, cut on a sustainable rotation and burnt for the ash ( and consequently when seaweed prices dropped, a main cause of emigration to Nova Scotia and New Zealand).

Keeping up a crofting lifestyle in the 21st century must still be hugely challenging. I may be enjoying the long evenings, but I’m keenly aware that farming a croft here through a short summer season (and did I mention the wind) and long winter nights must require extraordinary resilience, something my host definitely evidences.

Croft life

While my host knits (I’ve already been gifted a marvellous pair of made-to-measure stripey socks), or we work together on a jigsaw, I take the opportunity to ask about her early life. I hear of the men in the military camps near the village in WWII, stationed on this close outpost for the north Atlantic shipping route, whose presence brought new improved shops, but also of the exhausting work of harvesting peat. It’s no wonder, I think to myself, that Morag delights in her oil-fired central heating ( and fortunately for me, puts it on some evenings for an hour or two). I’ve walked up to the area of distant moorland hillside where, after several weeks of drying, she and her late husband would take the horse and cart to bring home the cut peat slabs, and seen how big a stack must be to last the winter (curiously once dried, the peat blocks are impervious to rain so at least no cover is needed).

I learn of the joy in the village in 1959, the year piped water arrived at each house. A decade later household electricity was rolled out (one local house apparently already had the television, set up and ready to go)! I hear of the challenge of the old houses, built with no damp course, and floors of sand so soft that rats could burrow through, and the pleasure of moving to the current house which her husband built to modern standards in 1985 after he retired.

At my table under the dormer window of my upstairs bedroom, I can watch sheep grazing on this croft land. it’s an 8-acre strip of land about 40 metres wide, parallelled by other similar croft strips on each side. Inherited from her father, it stretches from the machair area near the dunes past her old house, across the road and past her current home to the edge of the peat moorland, an area for communal grazing and peat cutting. As I walk this moorland area one afternoon, I sight a glorious red deer stag, yet although red deer at today’s population levels are environmentally destructive, they are ‘hands off’: all deer as well as the salmon and brown trout in the freshwater lochs are the property of the island’s private owner. Shooting and fishing remain the sport of the owners’ guests and wealthy paying visitors from England, the USA and elsewhere.

English is a 2nd language

Morag’s first language is Scots Gaelic. Fortunately for me though, she’s bilingual in English, first encountered when she started school, and spoken with a gentle Scottish cadence. I get the opportunity to listen to the lilting to and fro flow of Scots Gaelic conversations. I’m fascinated how there is a space for each party to affirm the other’s viewpoint, and then for the original speaker to affirm the affirmation! (The Scots Gaelic term for this way of connecting apparently translates as ‘yes, good’; I now hanker for spaces where such ‘yes, good’ affirmations of affirmations become a norm for speakers of English too, a step I believe would deepen our connections one to another).

Learning Scots Gaelic presents me a huge challenge. I struggle to achieve more than a few phrases, not aided by how it seems to sounds nothing like it looks! Like te reo Māori, Scots Gaelic (pronounced ‘Gallic’) is a language that is only now getting the full honour it deserves. Dual language signposts throughout the Highlands and Islands make clear how this is a language with a future.

Indeed even the Scots Gaelic name of the settlement where Morag lives seems impossible! Well, how would you say, ‘ An Ceathramh Meadhanach’ ? Yet though I still need to explain where I stay by it’s English name of ‘Middle Quarter’ for now, I’m in no doubt how fortunate I am to be here.

As the Nonviolent Communication approach points out, ‘There is no greater joy in life than to enhance the wellbeing of another’. It sums up my HelpX role here. Tomorrow I’ll continue the sand and repaint of Morag’s repurposed old church pew, now a place for her to sit for a while each day outside in the sun (relatively sheltered from the wind, not that locals seem to notice it like I do!) Despite regular rain showers and wind ( did I mention the wind), the bench appears to be progressing. Albeit with imperfections.

Where next?

It will be hard to leave. However in mid-August, I’ll load my bike once more and head for the causeway to the island of Berneray. There to rejoin the northern section of the ‘Hebridean Way’ cycle route with a ferry journey to the island of Harris. I will then follow the hills to the ‘Butt of Lewis’, the northern most point in the Hebridean chain. So popular though is the route with cyclists and others that much of the accommodation is booked out, so I hope I’m ready for the challenges of camping. One night last month in the tent my daughter lent me gives me hope, but I’ve ordered a new set of guy ropes online. Did I mention how the wind here seems, er , surprising?

Wind notwithstanding, spending time here seems fitting. After all, it was the former ‘New Hebrides’ (Vanuatu) that first drew me away from the United Kingdom 40 years ago, now it’s the ‘old’ Hebrides that draws me back. In both island chains, humans and non-humans alike that I’ve had the honour of encountering seem supremely well-adapted to their unique environments. Now of course new external forces threaten their traditional existence, indeed their existence full stop. Tackling the effects of climate breakdown, political power-plays, and rising sea lvels will require fortitude, wisdom and resilience. Fortunately all three seem hallmarks of these island communities: I have a very real sense that if anyone has the capacity to rise to such challenges, these people will.

Leave a comment